Dermatitis, Diarrhea and Alopecia: What Is Your Diagnosis?

History and Clinical Presentation A 36-year-old black woman presents to the

emergency room with the chief complaint of a desquamating, painful skin

rash around her mouth, abdomen, groin, inner thighs, and buttocks, which

has been present for the past 8-10 days. She also noticed increased

peeling of the skin on her hands and feet. The patient has not been able

to eat normally for a few days because of increasing tongue pain.

History Eight years ago she had gastric bypass

surgery and has lost more than 230 lb. Since her surgery, she has

suffered from chronic abdominal pain and diarrhea as a result of short

gut syndrome, and she reports worsening of diarrhea for the past 4

months. The patient also complains of chronic, progressive hair loss.

Physical Examination Physical exam reveals large, red-brown

plaques with desquamating sheets of scale and underlying superficial

erosions and denuded tissue on the patient's buttocks (Figures 1 and 2)

and inner thighs (Figure 3). On oral exam, similar perioral, red-brown

desquamation and smooth, edematous glossitis are seen (Figure 4).

Desquamation is also evident on the palms of her hands (Figure 5) and

soles of her feet. Diffuse, patchy, nonscarring alopecia is present on

the scalp.

Figure 1.

Figure 1. Red-brown plaques and desquamation of patient's buttocks.

Figure 2.

Figure 2. Red-brown plaques and desquamation of patient's buttocks.

Figure 3.

Figure 3. Plaques and desquamation of patient's upper thigh.

Figure 4.

Figure 4. Perioral plaques and glossitis.

Figure 5.

Figure 5. Palms of hands, showing skin desquamation.

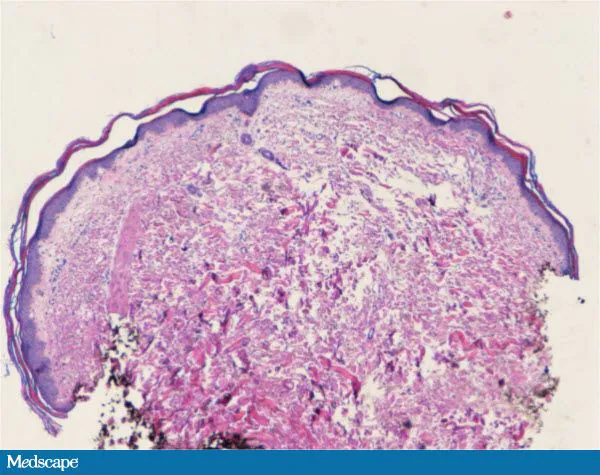

Diagnostic Evaluation Histopathology On hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain,

atrophic epidermis with palor high and confluent parakeratosis and

alternating orthokeratosis are visualized. The keratinocytes within the

epidermis are relatively normal (Figures 6 and 7).

Figure 6.

Figure 6. H&E stain, low magnification (10x).

Figure 7.

Figure 7. H&E stain, high magnification (40x).

What is your diagnosis?

- Lichen planus

- Mastocytosis

- Necrolytic acral erythema

- Glucagonoma syndrome

- Acquired zinc deficiency

- Diagnosis

Laboratory Studies

The patient's glucagon level was within

normal limits and hepatitis C antibody levels were negative. Measurement

of serum zinc revealed a level that was below normal limits at 50 μg/dL

(normal range, 70-150 μg/dL).

Discussion: The Missing Zinc

Given the clinical, histologic, and

laboratory findings, the patient was diagnosed with acquired zinc

deficiency and associated exfoliative dermatitis.

Zinc is one of the most important elements in

the human body, mediating the production of lipids, proteins, and

nucleic acids. It also plays an essential role in normal wound healing,

reproduction, cardiovascular health, olfaction, and immunity. The

recommended daily allowance of zinc is 15 mg but can range from 3 to 25

mg depending on age.[1-3]

A wide variety of foods contain zinc. Amounts of zinc contained in food

are determined by the protein content of the food source. Oysters

contain higher levels of zinc per serving than any other nutritional

source. Other excellent sources include beans, whole grains, nuts, green

leafy vegetables, and dairy products.[1,2]

Zinc deficiency is divided into acquired and

genetic forms. Acrodermatitis enteropathica (the genetic form) is

inherited in an autosomal recessive fashion.[4] Mutations in the transmembrane zinc transporter protein SLC39A4 on chromosome 8 affect normal intestinal absorption of zinc.[5,6]

Children affected by this condition usually present with periorificial

and acral erythematous, scaly plaques, diarrhea, and alopecia within the

first few months of life as breast-feeding is discontinued.[4,7] Secondary infection with Staphylococcus aureus or Candida albicans is also common.[2]

Acquired zinc deficiency is seen in

association with a number of conditions affecting either zinc intake or

absorption (such as high-fiber diets, poor nutritional intake,

malabsorption syndromes, and gastrointestinal disease) or excessive zinc

losses, including alcoholism, malignancy, pregnancy, drugs

(penicillamine), and extensive burns.[2,3]

Acquired forms of zinc deficiency can look fairly similar to genetic

forms upon presentation, with the classic triad of exfoliative

dermatitis, diarrhea, and alopecia. The condition can be further

complicated by impaired immunity, poor wound healing, anorexia, or

delayed puberty.[1,2,8]

Zinc deficiency is diagnosed by the classic

triad of clinical features (dermatitis, diarrhea, and alopecia),

histologic findings (epidermal atrophy and necrosis) and low plasma zinc

levels. Most patients will have plasma zinc levels below 60 μg/dL.[1]The differential diagnosis includes glucagonoma and necrolytic acral erythema secondary to hepatitis C infection.[2]

After the diagnosis of zinc deficiency is confirmed, zinc should be

supplemented at a dose of 1-3 mg/kg/day for life. Response to treatment

is fairly rapid; improvement in cutaneous findings can be seen as early

as 1-2 weeks.[1-3]

Follow-up

The lower small bowel absorptive area in this

patient following her bariatric procedure led to her acquired zinc

deficiency. She was admitted to the hospital for nutritional support,

intravenous fluids, and zinc supplementation. Her exfoliative dermatitis

dramatically improved after only 15 days of zinc supplementation

(Figure 8).

Figure 8. Improvement in cutaneous findings between presentation (day 1) and almost 3 weeks of treatment (day 20).