Craniofacial, Unilateral Cleft Lip Repair cleft lip repair,cleft,lip,plastic,repair,cleft lip,cleft,lip,repair cleft lip,plastic repair,cleft lip,cleft,cleft,unilateral,cleft,bilateral,cleft lip,repair,cleft,lipBackgroundThe

presence of unilateral cleft lip is one of the most common congenital

deformities. A broad spectrum of variations in clinical presentation

exists. Unilateral cleft lip involves deformity of the lip in addition

to the alveolus and nose. Patients with this deformity require

short-term care and long-term care and follow-up from practitioners in

multiple specialties.

[1] Patients

may need multiple surgical interventions, from infancy to adulthood, in

order to achieve necessary function and aesthetic quality. No

universal agreement has been reached as to the timing and technique of

repair. Several methods are used with comparable long-term results,

which serves as an indication that more than one treatment option exists

for definitive repair. Treatment goals include the restoration of

facial appearance and oral function, improvement of dental skeletal and

occlusal relationships, improvement of speech, and the psychosocial

state.

Next Section: History of the Procedure

History of the ProcedureIn

1843, closure of the unilateral cleft lip with local flaps was

described by Malgaigne. The following year, Mirault modified Malgaigne’s

technique by using the lateral lip flap to fill the medial defect. All

future methods of cleft lip closure are based on Mirault’s technique.

LeMesurier and Tennyson modified this technique with a quadrilateral and

triangular flap, respectively. In 1976, Millard published his

definitive repair in which the lateral flap advancement into the upper

portion of lip was combined with downward rotation of medial lip.

[2] Other modifications have been published by Noordhoff, Mohler, and Onizuka.

[3, 4] Fisher

has described an anatomical subunit approximation for definitive cleft

lip repair. Millard’s methods, including variations, remain among the

most popular method for unilateral cleft lip closure.

[4] Cleft

lip surgery has evolved from a simple adhesion of paired margins of the

cleft to an understanding of the various malpositioned elements of the

lip to a more complicated geometric reconstruction using transposition,

rotation, and advancement flaps.

[5] Previous

Next Section: History of the Procedure

ProblemThe

cleft affects the facial form as an anatomic deformity and has

functional consequences. These include the child's ability to eat,

speak, hear, and breathe. Consequently, rehabilitation of a child born

with a facial cleft must involve a multidisciplinary approach and staged

appropriately with the child's development, balancing the timing of

intervention against its effect on subsequent normal growth.

Previous

Next Section: History of the Procedure

Epidemiology

FrequencyThe

overall occurrence of cleft lip with or without cleft palate is

approximately 1 in 750-1000 live births. Racial differences exist, with

the incidence in Asians (1:500) greater than in Caucasians (1:750)

greater than in African Americans (1:2000). The incidence of cleft

lip/palate is more common in males.The most common presentation is cleft lip and palate (approximately 45%), followed by cleft palate alone (35%) and cleft lip alone (approximately 20%). Unilateral cleft lips are more common than bilateral cleft lips and occur more commonly on the left side (left cleft lip:right cleft lip:bilateral cleft lip = 6:3:1).The

risk of a newborn having a cleft lip increases if a first-degree

relative also has a cleft. If one child already has a cleft lip, the

chance of a second child being born with the deformity is 4%. If a

parent has a cleft lip, the chance of a newborn having a cleft is 7%. If

both a parent and a sibling have a cleft lip, the newborn's risk rises

to 15%.

Previous

Next Section: History of the Procedure

EtiologyClefting has a multifactorial basis, with both genetic and environmental causes

cited. The observation of clustered cases of facial clefts in a

particular family indicates a genetic basis. Clefting of the lip and/or

palate is associated with more than 150 syndromes. The overall incidence

of associated anomalies (eg, cardiac) is approximately 30% (more common

with isolated cleft palate).Environmental causes, such as viral infection (eg, rubella)

and teratogens (eg, steroids, anticonvulsants), during the first

trimester have been linked to facial clefts. The risk also increases

with parental age, especially when older than 30 years, with the

father's age appearing to be a more significant factor than the mother's

age. Nevertheless, most presentations are of isolated patients within

the family without an obvious etiology.Midfacial development

involves several sets of genes, including those involved in cell

patterning, proliferation, and signaling. Mutations in any of these

genes can change the developmental process and contribute to cleft

development. Some of these genes include the

DIX gene, sonic hedgehog (

SHH) gene, transforming growth factor (

TGF) alpha/beta, and interferon regulatory factor (

IRF6).

Classification

Kernahan developed a classification scheme in which the defect can be classified

onto a Y-shaped symbol. In this diagram, the incisive foramen is

represented as the focal point. This system has been applied to both

cleft lip and palate

.

Millard

modification of Kernahan striped-Y classification for cleft lip and

palate. The small circle indicates the incisive foramen; the triangles

indicate the nasal tip and nasal floor.

Previous

Next Section: History of the Procedure

PathophysiologyWhile the normal embryologic development of the face is detailed in Head and Neck Embryology, a brief outline relevant to the formation of facial clefts follows.In

short, the branchial arches are responsible for the formation of

several areas, including the mouth and lip. Mesenchymal migration and

fusion occurs during weeks 4-7 of gestation. The first branchial arch is

responsible for the formation of the maxillary and mandibular

processes. The maxillary and mandibular prominences form the lateral

borders of the primitive mouth or stomodeum.Mesenchymal migration

and fusion of the primitive somite-derived facial elements (central

frontonasal, 2 lateral maxillary, mandibular processes), at 4-7 weeks

gestation, is necessary for the normal development of embryonic facial

structures. When migration and fusion are interrupted for any reason, a

facial cleft develops along embryonic fusion lines. The embryonic

development of the primary palate (lip and palate anterior to the

incisive foramen) differs from the secondary palate (palate posterior to

the incisive foramen).The developing processes of the medial

nasal prominence, lateral nasal prominence, and maxillary prominences

form the primary palate. Fusion occurs, followed by "streaming" of

mesodermal elements derived from the neural crest. In contrast, the

secondary palate is formed by the fusion of palatal processes of the

maxillary prominence alone. The difference in embryonic development

suggests the possibility of differing degrees of susceptibility to

genetic and environmental influences and accounts for the observed

variation in incidences.In summary, unilateral cleft lip results from failure of fusion of the medial nasal prominence with the maxillary prominence.

Previous

Next Section: History of the Procedure

PresentationFor

treatment purposes, unilateral cleft lip can be placed into one of

three categories: microform/forme fruste, incomplete, or complete cleft

lip.

- Microform cleft (forme fruste):

This defect is characterized by a "light" furrow along the vertical

length of the lip with a small vermilion notch and minor imperfections

in the white roll. A small component of vertical lip length deficiency

and associated nasal deformity may be present.

- Incomplete

cleft lip: This defect is characterized by the varying degree of

vertical lip separation. By definition, it has an intact nasal sill,

commonly termed the Simonart band.

- Complete

cleft lip: This involves the full-thickness defect of the lip and

alveolus (primary palate), extends into the base of the nose (no

Simonart band exists), and is often accompanied by a palatal cleft

(secondary palate). The premaxilla is typically rotated outward and

projects anteriorly in relation to a relatively retropositioned lateral

maxillary alveolar element.

As a consequence of the

clefting of the lip, an associated nasal deformity occurs. The

structures of the ala base, nasal sill, vomer, and septum are distorted

significantly. The lower lateral cartilage on the cleft side is

positioned inferiorly, with an obtuse angle as it flattens across the

cleft. The alar base is rotated outward. The developing nasal septum

pulls the premaxilla away from the cleft, and the septum and the nasal

spine are deflected toward the noncleft side. The cleft may continue

through the maxillary alveolus and palatal shelf, extending to the

palatal bone and soft palate.

Further treatment planningOrthodontic treatment can be initiated a few weeks following birth, prior to

surgical intervention. Other adjunct procedures include lip adhesion,

presurgical orthopedics, primary nasal correction, and nasoalveolar

molding. These procedures attempt to reduce the deformity. Nasoalveolar

molding is the active molding and repositioning of the nasal cartilage

and alveolar processes with an appliance.

[6] This

orthodontic intervention takes advantage of the plasticity of the

cartilage. Presurgical nasal alveolar allows repositioning of the

maxillary alveolus and surrounding soft tissues in hopes of reducing

wound tension and improving results.

[7, 8] Definitive

repair is delayed until approximately 3 months of age; this varies,

depending on physician comfort. A multidisciplinary approach should be

carried out over several years for patients with unilateral cleft lip.

This team should include practitioners from audiology, otolaryngology,

and speech therapy, among other specialities.

Previous

Next Section: History of the Procedure

IndicationsPatients

born with a cleft lip should undergo surgical repair unless otherwise

contraindicated. The goal of reconstruction is to establish normal

morphologic facial form and function in order to provide the optimal

conditions for the development of dentition, mastication, hearing,

speech, and breathing, and psychosocial status.

Previous

Next Section: History of the Procedure

Relevant AnatomyNormal

lip and nasal anatomy is essential for an understanding of the

distortion caused by a facial cleft. The elements of the normal lip are

composed of the central philtrum, demarcated laterally by the philtral

columns and inferiorly by the Cupid's bow and tubercle. Just above the

junction of the vermilion-cutaneous border is a mucocutaneous ridge

frequently referred to as the white roll. Within the red vermilion of

the lip is a noticeable junction demarcating the dry and wet vermilion,

the increased keratinized portion of the lip that is exposed to air from

the moist environment of the labial mucosa. The primary muscle

of the lip is the orbicularis oris, and it has two well-defined

components: the deep (internal) and the superficial (external)

components. The deep (internal) fibers run horizontally or

circumferentially from commissure (modiolus) to commissure (modiolus)

and functions as the primary sphincteric action for oral feeding. The

superficial (external) fibers run obliquely, interdigitating with the

other muscles of facial expression to terminate in the dermis. They

provide subtle shades of expression and precise movements of the lip for

speech. The superficial fibers of the orbicularis decussate in

the midline and insert into the skin lateral to the opposite philtral

groove forming the philtral columns. The resulting philtral dimple

centrally is depressed as there are no muscle fibers that directly

insert into the dermis in the midline. The tubercle of the lip is shaped

by the pars marginalis, the portion of the orbicularis along the

vermilion forming the tubercle of the lip with eversion of the muscle. In

the upper lip, the levator labii superioris contributes to the form of

the lip. Its fibers, arising from the medial aspect of the infraorbital

rim, sweep down to insert near the vermilion cutaneous junction. The

medial-most fibers of the levator labii superioris sweep down to insert

near the corner of the ipsilateral philtral column and

vermilion-cutaneous junction, helping to define the lower philtral

column and the peak of the Cupid's bow. The nasal muscles are

equally important. The levator superioris alaeque arises along the

frontal process of the maxilla and courses inferiorly to insert on the

mucosal surface of the lip and ala. The transverse nasalis arises along

the nasal dorsum and sweeps around the ala to insert along the nasal

sill from lateral to medial into the incisal crest and anterior nasal

spine. These fibers join with the oblique fibers of the orbicularis and

the depressor septi (nasalis), which arises from the alveolus between

the central and lateral incisors to insert into the skin of the

columellar to the nasal tip and the footplates of the medial crura. A

unilateral cleft thus disrupts the normal termination of the muscle

fibers that cross the embryologic fault line of the maxillary and nasal

processes, resulting in symmetric but abnormal muscular forces between

the normal equilibrium that exists with the nasolabial and oral groups

of muscles. With an unrestrained premaxilla, the deformity accentuates

with differential growth of the various elements. The alar cartilages

are splayed apart and rotate caudally, subluxed from the normal

position. Consequently, the nasal tip broadens, the columellar is

foreshortened, and the alar bases rotate outwardly cephalad.

Previous

Next Section: History of the Procedure

Contraindications

- Malnutrition,

anemia, or other pediatric conditions that result in the patient's

inability to tolerate general anesthesia are contraindications to this

procedure.

- Cardiac anomalies that may coexist must be addressed prior to the lip repair

Craniofacial, Unilateral Cleft Lip Repair WorkupLaboratory Studies

- Perform

a thorough physical examination, not limited to the head and neck

region, to uncover associated anomalies in the infant presenting with a

unilateral cleft lip with or without a palatal cleft. Additional workup

is determined by physical findings that suggest involvement of other

organ systems.

- The child's weight, oral intake, and growth and/or development are of primary concern and must be followed closely.

- Routine laboratory studies typically are not required, other than a hemoglobin study shortly before the planned lip repair.

- Routine imaging is not indicated in a healthy patient with isolated cleft lip.

- Craniofacial, Unilateral Cleft Lip Repair Treatment & Management

- Surgical Therapy

Children

born with a facial cleft benefit from multidisciplinary clinical care.

This is a team-based approach allowing efficient coordination of all

aspects of care. Beyond the lip repair are other issues such as hearing,

speech, dental, and psychosocial integration. With the

multidisciplinary approach, as the child grows, comprehensive care can

be given from birth through adolescence. These associated issues are as

important as the anatomic reconstruction, and ultimately the functional

outcome of the reconstruction depends on addressing them. Each

specialty involved must evaluate the child individually and formulate a

treatment plan, then the team forms a combined individual integrated

protocol that follows the Parameters of Care Guidelines established by

the American Cleft Palate Craniofacial Association. Rather than strictly

adhering to any one protocol, each child is assessed based on the

present need in his or her development, and a treatment plan is created

based on the team's experience.

Next Section: Preoperative Details

Preoperative Details

While

the lip repair is the initial focus for many parents, treatment begins

by assessing the child's nutritional status and assisting the parents

with oral feeding techniques so that appropriate weight gain occurs. Parents

who suddenly are faced with caring for a child with a facial cleft are

overwhelmed. The importance of spending sufficient time with them to

allay their fears, to discuss staging and timing of reconstruction, to

stress the need for involvement of other specialists, and to instruct

them on the importance of long-term and consistent follow-up care from

birth through adolescence cannot be overemphasized. The optimal

timing of the surgical repair is still somewhat controversial. Some

centers have advocated surgery in the early neonatal period, with a

theoretical benefit in the scar appearance and nasal cartilage

adaptability, thus minimizing the nasal deformity. To minimize

anesthetic risks, some still adhere to the rule of 10s: perform surgical

repair of cleft lip when the child has a hemoglobin of 10 g, weight of

10 lb, and is aged 10 weeks. In general, however, most centers prefer to

perform the unilateral lip repair when the infant is aged 2-4 months;

anesthesia risks are lower, the child is better able to withstand the

stress of surgery, and lip elements are larger and allow for a

meticulous reconstruction. Before the definitive lip surgery,

cleft centers utilize lip taping, alone or in combination with a passive

intraoral appliance or an active pin-based appliance (eg, Latham) to

align the maxillary arch segments; or no presurgical orthopedic

intervention at all. This choice depends on the center's protocol and

resources. A number of cleft centers prefer to use a passive

intraoral orthodontic palatal appliance to maintain the arch width to

prevent the nearly inevitable collapse that occurs with the lip surgery.[6] The

lip repair reestablishes the soft tissue and muscular forces on the

easily moldable maxillary arch segments. Additionally, this appliance

may include a nasal extension to help improve the nasal tip form. This

nasal alveolar molding device is incorporated into the intraoral

appliance. Several weeks of treatment prior to the surgery and regular

adjustments are needed to mold the alar cartilages into a more favorable

position, thus facilitating the surgical correction of the nasal

deformity. Impressions are taken soon after birth so that the custom

appliance can be applied as soon as possible before the lip repair. The

appliance also assists in the child's oral feeding, helping to decrease

nasal regurgitation and assisting oral suction.

Previous

Next Section: Preoperative Details

Intraoperative Details

The

ideal lip repair results in symmetrically shaped nostrils, nasal sill,

and alar bases; a well-defined philtral dimple and columns; and a

natural appearing Cupid's bow with a pout to the vermilion tubercle. In

addition, it results in a functional muscle repair that with animation

mimics a normal lip. While ideally the lip scars approximate natural

landmarks, ultimately the eye first focuses on symmetry and then normal

contours of the lip at rest and in animation. A number of

surgical procedures for the repair of a unilateral cleft lip are well

described, with a multitude of variations, including the LeMesurier

quadrilateral flap repair, Randall-Tennison triangular flap repair,

Millard rotation-advancement repair,[9] and

Skoog and Kernahan-Bauer upper and lower lip Z-plasty repairs. Many

other variations exist; of particular note are the repairs by Delaire

and by Poole

- .

- The Rose-Thompson repair involves curved or angled paring of the cleft margins to lengthen the lip as a straight-line closure.

Hagedorn-LeMesurier

Hagedorn-LeMesurier

repair. The medial lip element is lengthened by introducing a

quadrilateral flap developed from the lateral lip

- element.

-

- Tennison-Randall

repair. The medial lip element is lengthened by introducing a

triangular flap from the inferior portion of the lateral

- lip element.

-

- Skoog

repair. The medial lip element is lengthened by introducing two small

triangular flaps developed from the lateral lip element. Each

of these techniques ultimately has the common goal of achieving

symmetry and restoring the continuity of the underlying orbicularis

muscle. All attempt to lengthen the foreshortened philtrum on the cleft

side by interposing tissue from the lateral lip element into the medial

lip element through various combinations of rotation, advancement, and

transposition flaps. While none of the repairs is ideal, each has

advantages and disadvantages, and each results in an excellent repair

in experienced hands, underscoring the fact that more than a single

acceptable technique, rather than a single ideal repair, is available.

However, because of the limitations of this article, the authors choose

to focus on the repair Millard first described in 1955, as today it is

perhaps the most commonly adapted repair of cleft lip. The

rotation-advancement method of Millard advances a mucocutaneous flap

from the lateral lip element into the gap of the upper portion of the

lip resulting from the inferior downward rotation of the medial lip

element.[9] The

repair attempts to place the lip scars along anatomic lines of the

philtral column and nasal sill. Conceptually, Millard's approach is

elegant but it is not always technically easy to accomplish without some

modifications to deal with the wide variation in clefts. As with any

other repair, consistency in achieving a good result is

operator-dependent. A cursory description of a modified Millard operative technique used by the authors is as follows:

- Use

general anesthesia with a noncuffed oro-Rae endotracheal tube

positioned midline. Typically the otolaryngologist then examines the

ears; if needed, myringotomy and pressure equalizing tubes are placed.

- Prior

to infiltration with a local anesthetic (0.5% lidocaine with 1:200,000

epinephrine), mark the anatomic landmarks and tattoo them with a

methylene blue dye.

-

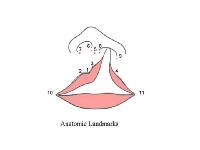

- Figure

illustrates important anatomic landmarks used in all cleft lip repairs.

Measurements of various distances are used to guide the surgeon in

creating a symmetric lip.

- Two

key elements are involved in the markings: the placement of the final

position of the new Cupid's bow peak and the vertical length of the

philtral column to be created on the cleft side. Referring to the

diagram, Point 3 is determined as the mirror image of Point 2 based on

the distance from the midpoint to the peak of the Cupid's bow on the

noncleft side. The peak on the cleft side, Point 4, is not determined as

easily but typically is placed level with Point 2, where the dry

vermilion is widest and the white roll above is well developed. The

white roll and dry vermilion taper off medial to this point. It is

unreliable to determine the peak on the cleft side using the distance

between the peak of the Cupid's bow from the commissure on the noncleft

side because of unequal tension of the underlying orbicularis muscle.

- Once

the anatomic points are marked, draw incision lines that define the 5

flaps involved in the lip reconstruction. These are the inferior

rotation flap (R) of the medial lip element, the medial advancement flap

(A) of the lateral lip element, the columellar base flap (C) of the

medial lip element, and the two pared mucosal flaps of the medial (m)

and lateral (l) lip elements. Two additional flaps that refine the

repair often are used: a white roll flap and a vermilion triangular flap

to allow for a smoother transition at the vermilion cutaneous junction

and at the vermilion contour.

- The

essential marking is the line that determines the border between the R

and C flaps. This line becomes the new philtral column on the cleft

side. For the vertical lengths of the philtrum on the cleft side and

noncleft side to be symmetric, the length of the rotation advancement

flap (y) should equal the vertical length of the philtral column (x) on

the noncleft side (distance between alar base and Cupid's bow peak). For

the two lengths, x and y, to be equal, the path of y must be curved as

illustrated. In marking the curve, take care to avoid a high arching

curve that comes too high at the columellar base to create a generous

philtrum, as this significantly diminishes the size of the C flap.

- While

all flaps are marked, the authors typically refine the design of the A

flap after the R and C flaps are repositioned appropriately so that it

more accurately is tailored to fill the gap left by the inferior

rotation of the R flap and the final placement of the C flap.

- Pare

the margins of the cleft and develop the m and l flaps. The l flap can

be used to inset into the nasal vestibule lining, and the m flap can be

used as part of the orolabial vestibule lining as needed. Alternatively,

both flaps can be used to reconstruct the nasal and orovestibular

lining of the nasal floor depending on the situation. The pars

marginalis of the orbicularis typically is tethered by its abnormal

insertion and further is pared, allowing the constricted muscle to

expand.

- In the region of the

vermilion-cutaneous junction, incise the muscle for approximately 2-3 mm

on either side of the cleft paralleling the vermilion border to allow

development of vermilion-cutaneous muscular flaps for final alignment.

- Develop

the R and C flaps by incising the line (x) between the flaps to allow

inferior rotation of the R flap so that it lies horizontally tension

free with Point 3, level with Point 2. For this to occur, release must

be at all levels (skin, subcutaneous tissue, muscle, fibrous attachments

to the anterior nasal spine, labial mucosa). Occasionally an additional

1- to 2-mm back cut just medial to the noncleft philtral column is

required along with a mucosal back cut to allow for adequate inferior

rotation of the R flap. The back cut occasionally can be limited to the

subdermal portion to avoid lengthening the

- cutaneous scar.

-

- Millard

repair. With maximal rotation of the R flap, any residual lip length

discrepancy can be corrected with an inferior Z-plasty or a triangular

flap. In a secondary correction, further rotation of the R flap can be

considered.

- Correspondingly

free the C flap with the medial crus of the alar cartilage and allow it

to be repositioned, creating a large gap to be filled by the A flap.

- Develop

the A flap from the lateral lip element for advancement into the gap

between the R and C flaps. In developing the A flap, keep the incision

along the alar base at a minimum; it rarely is required to extend much

beyond the medial-most aspect of the alar base. The key to allowing

adequate mobilization of the A flap is the subcutaneous release of the

fibrous attachments of the alar base to the piriform margin of the

maxilla and not necessarily a continued cutaneous incision along the

alar margin. Other surgeons have chosen to mobilize the ala at the

subperiosteal level.

-

- Millard

repair. The medial lip element [R] is rotated inferiorly and the

lateral lip element [A] is advanced into the resulting upper lip defect.

The columellar flap [C] is then used to create the nasal sill (see text

for details).

- A

lateral labial mucosal vestibular release also is required to mobilize

the A flap medially and to avoid a tight-appearing postoperative upper

lip deformity. Do not forget that the maxillary alveolar arches

typically are at different heights in the coronal plane, and the ala

must be released completely and mobilized superior medially to achieve

symmetry, although ultimately its maxillary support is inadequate until

arch alignment and bone grafting can be accomplished.

- As

part of the mobilization of the ala, make an incision along the nasal

skin-mucosal vestibular junction (infracartilaginous) where the

previously developed l flap may be interposed if needed. Currently, the

trend is toward more aggressive mobilization and repositioning of the

lower lateral cartilages as an integral part of the cleft lip repair.

- Widely

undermine the nasal tip between the cartilage and the overlying skin

approaching laterally from the alar base and medially from the

columellar base.

- While the A flap

can be inserted as a mucocutaneous flap incorporating the orbicularis,

the authors repair the muscle separately to allow for differential

re-orientation of its vectors. Dissect the muscle from the overlying

skin and the underlying mucosa to accomplish this and divide it into

bundles that can be repositioned and interposed appropriately.

- Once

all the flaps are developed and the medial and lateral lip elements are

well mobilized, begin reconstruction. Typically, this begins with

creating the labial vestibular lining from superior to inferior and then

proceeding to the junction of the wet-dry vermilion with completion of

the remainder of the vermilion after the cutaneous portion of the lip is

completed.

- At this point, the

labial mucosa can be advanced as needed, with additional lengthening and

a back cut to allow for adequate eversion of the lip and to avoid a

tight-appearing lip postoperatively.

- Direct

attention to approximating the muscle bundles. Appropriately reorient

the nasolabial group of muscles toward the nasal spine. Follow this by

approximating the orbicularis, interdigitated with its opposing element

along the full length of the vertical lip. Inset the C flap to create a

symmetric columellar length and flare at its base. Millard originally

described the C flap to cross the nasal sill to insert into the lateral

lip element as a lateral rotation-advancement flap. Millard later

refined the C flap as a medial superior rotation flap to insert into the

medial lip element, augmenting the columellar height and creating a

more natural flare at the base of the medial footplate. The latter

method occasionally results in a nexus of scars at the base of the

columellar with unfavorable healing if the flaps are not well planned.

However, the authors and others continue to use the C flap in either

position as needed.

-

- Millard

repair. Two of the most common variations described with utilization of

the C Flap to correct the hemi-columellar deficiency (Millard II] and

the nasal sill alar base region [Millard I]

- Set

the ala base in place. As the C and A flaps and the ala are inset, take

care to leave an appropriate width to the nasal sill to avoid a

constricted-appearing nostril, which is nearly impossible to correct as a

secondary deformity.

- Approximate

the vermilion-cutaneous junction and inset the vermilion mucocutaneous

triangular flap. If the lip appears to be vertically short at this

point, the authors inset a small, 2- to 3-mm triangular flap into the

medial lip just above the vermilion.

- Use

dermal sutures to approximate the skin edges. Final approximation is

with either rapidly absorbing sutures or nylon sutures, ideally removed

at 5 days. If the cutaneous edges are well approximated with dermal

sutures alone, the authors occasionally use a cyanoacrylate-type

adhesive. Reposition the cleft alar cartilage with

suspension/transfixion sutures and a stent. Further shape the ala with

through-and-through absorbable sutures as needed.

Previous

Next Section: Preoperative Details

Postoperative Details

- Oral

feedings: For the child who is breastfed, the authors encourage

uninterrupted breastfeeding after surgery. Bottle-fed children can

resume feedings immediately following surgery with the same crosscut

nipple used before surgery. Some centers still advocate having the child

use a soft catheter-tip syringe for 10 days and then resuming normal

nipple bottle feeding, but the authors have found this degree of caution

to be unnecessary.

- Activities: The authors instruct

the parents to avoid giving the child pacifiers or toys with sharp

edges for 2 weeks after surgery. No other particular restrictions on

activity are necessary. Some centers do advocate the use of Velcro elbow

immobilizers on the patient for 10 days to minimize the risk of

inadvertent injury to the lip repair. These are periodically removed

several times a day under supervision.

- Lip care: The

exposed suture line at the base of the nose and red lip can be cleaned

using cotton swabs with diluted hydrogen peroxide, and topical

antibiotic ointment can be applied several times a day. The authors then

remove the permanent sutures on postoperative day 5-7. If cyanoacrylate

adhesive is used, no additional care is required in the immediate

postoperative period until the adhesive film comes off. The authors tell

the parents to expect noticeable scar contracture, erythema, and

firmness 4-6 weeks postsurgery, and that this gradually begins to

improve 6-12 months after the procedure. Typically, the authors instruct

parents to massage the upper lip during this phase and to avoid placing

the child in direct sunlight until the scar matures.

Previous

Next Section: Preoperative Details

Follow-upFollowing

cleft lip repair, patients are evaluated periodically by the various

cleft team members. Oral hygiene and dental care must be promoted,

hearing and speech must be assessed, and psychosocial evaluation and

treatment should be made available. Despite technical advances

and simultaneous correction of the nasal deformity performed at the time

of lip repair, a significant number of patients still require a

secondary procedure to restore nasal symmetry and improve function.

[10] Such

procedures should be individualized. The alar base symmetry is unlikely

to be improved until the alveolar alignment is corrected and grafted

with bone. The remaining components of cleft care are addressed in other

articles, including the following:

- Cleft Lip and Palate

- Cleft Palate

- Craniofacial, Bilateral Cleft Lip Repair

- Craniofacial, Bilateral Cleft Nasal Repair

- Craniofacial, Unilateral Cleft Nasal Repair

- Cleft Lip Nasal Deformity

Previous

Next Section: Preoperative Details

ComplicationsSeveral

common mistakes are made in the rotation-advancement method of

unilateral cleft lip repair. These include insufficient rotation of the R

flap, vermilion-cutaneous mismatch, vermilion notching and a

tight-appearing lateral lip element, a lateral muscle bulge, a laterally

displaced ala, and a constricted-appearing nostril. Aside from

unsatisfactory appearance of the surgical result, possible complications

include dehiscence of the repair (more common if the repair is delayed

until the child is learning to walk and falls) and excessive scar

formation and/or contracture of lip scars. If dehiscence occurs,

postpone re-operation until the induration has subsided completely. With

lip scars that appear red, thick, and contracted, the authors use an

occlusive tape dressing and if needed, Kenalog-10 (triamcinolone

acetonide) injection and/or flurandrenolide tape. For most repairs, the

observed contracture is part of the normal healing process and improves

with time. Postpone revisional surgery until the scar matures.

Intervention should be guided by the severity of the residual deformity.

Keep revisions to a minimum.

Previous

Next Section: Preoperative Details

Outcome and PrognosisCareful

preoperative assessment of the cleft lip deformity and attention to

detail in the reconstruction typically results in an excellent repair

that achieves many characteristics of the natural lip. Realistically,

many variables are involved beyond the technical aspects of a particular

repair. Ultimately, the outcome depends on the natural course of

uncomplicated healing of the initial repair, alignment of the skeletal

framework on which the lip rests, and the differential effect of normal

growth and development on the operated lip. While a poor initial

result is unlikely to improve with time, do not assume that an excellent

initial result will not require some revisional procedure because of

uncontrolled variables. Moreover, while the lip repair may be

acceptable, additional procedures required to achieve nasal symmetry are

not uncommon, despite the initial primary nasal surgery incorporated as

an integral part of lip repair.

Previous

Next Section: Preoperative Details

Future and ControversiesCleft

lip surgery has evolved from a geometrically defined "cookie-cutter"

type approach to a more adaptable repair using the principles outlined

by Millard's elegant rotation advancement technique.

[9, 11] Skin

flap design has led to a better understanding of the underlying

musculature that is disrupted by the cleft and the importance of

realignment of the individual bundles to create a functional repair.

With a better understanding of the underlying anatomy, cleft surgery

currently results in an excellent lip repair but is marred by a residual

cleft nasal deformity.Adjunct treatment. including early

presurgical alveolar and nasal molding with a palatal appliance. may

improve the long-term outcome, with the ultimate intent to remove the

accompanying cleft nasal deformity, which is the most common stigmata of

a facial cleft.Only close long-term follow-up care and an honest assessment of the results can establish these improvements in outcome.

[1] Advances

in the treatment of children with clefts will come only from a

team-based approach in which close cooperation of multiple disciplines

can address all the child's needs. Such children deserve to be cared for

at major centers where an interdisciplinary approach is possible and

substantial experience is available.

</li>