Hepatitis C Virus Infection Among Adolescents and Young Adults

Abstract and Introduction IntroductionHepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a major cause of liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States.

[1,2] Of the estimated 2.7–3.9 million persons with active HCV infection,

most were born during 1945–1964 and likely were infected during the

1970s and 1980s, before the advent of prevention measures.

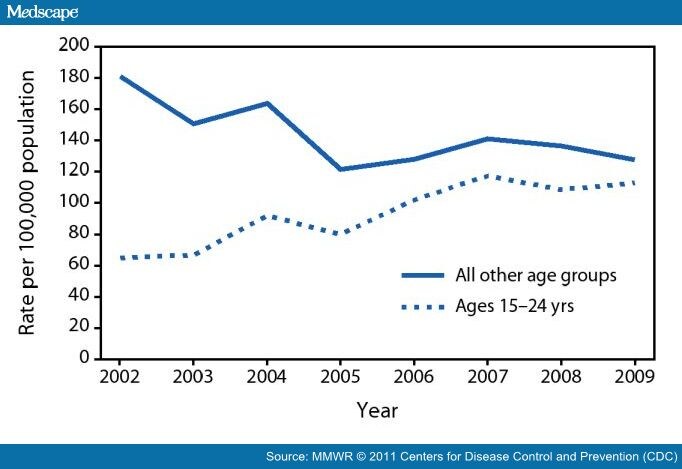

[3] Nationwide, rates of acute, symptomatic HCV infection declined during 1992–2005 and then began to level.

[4] Declines also were observed in rates of newly reported HCV infection in

Massachusetts. Although these declines were evident among reported

cases overall in Massachusetts during 2002–2006, an increase was

observed among cases in the 15–24 year age group. In response to this

increase, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health (MDPH) launched a

surveillance initiative to collect more detailed information on cases

reported during 2007–2009 among this younger age group and to examine

the data for trends through 2009. This report describes results of both

efforts, which revealed continued increases in rates of newly reported

HCV infection among persons aged 15–24 years. These cases were reported

from all areas of the state, occurred predominantly among non-Hispanic

white persons, and were equally distributed among males and females. Of

cases with available risk data, injection drug use (IDU) was the most

common risk factor for HCV transmission. The increase in case reports

appears to represent an epidemic of HCV infection related to IDU among

new populations of adolescents and young adults in Massachusetts. The

findings indicate the need for enhanced surveillance of HCV infection

and intensified hepatitis C prevention efforts targeting adolescents and

young adults.

MDPH currently uses an electronic data system for disease

surveillance. All positive laboratory results indicating HCV infection

are reportable to MDPH. A positive laboratory result on a previously

unreported case prompts a case report form to be sent to the health-care

provider (e.g., clinician) ordering the test. This one-page form

collects information on demographics, symptoms, and risk history. In

accordance with CDC case definitions, HCV infection cases are classified

as either confirmed (i.e., positive by an anti-HCV antibody assay with a

nucleic acid test [NAT] result confirming active infection) or probable

(i.e., positive antibody test result with confirmatory NAT either not

conducted or not reported to MDPH). For this analysis, all confirmed and

probable cases of HCV infection were included.

In 2006, anecdotal information received from community-based partners

about HCV infection cases among adolescents and young adults prompted a

review of state surveillance data. Although an overall decline in rates

of newly reported HCV infection (from 181 to 128 cases per 100,000

population) was observed during 2002–2006, an increase (from 65 to 102

cases per 100,000 population) was observed among persons aged 15–24

years. At the time, 75% of 2005 surveillance reports for cases among

persons in this age group lacked risk history; therefore, the sources of

infection were unknown. Beginning in 2007, MDPH sent HCV infection case

report forms (CRFs) to reporting clinicians to collect additional

information when a report of newly identified HCV antibody (anti-HCV)

positivity among persons aged 15–24 years was received. Clinicians also

were sent reminders to fill out CRFs if more than 30 days had passed

from the date the form was sent and a completed form had not yet been

received by MDPH.

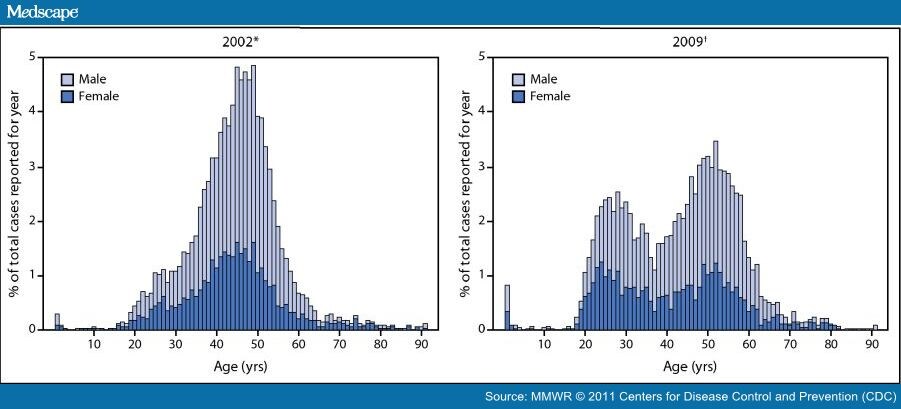

During 2002–2009, rates of newly reported HCV infection (confirmed

and probable) among persons aged 15–24 years increased from 65 to 113

cases per 100,000 population (Figure 1). The number of confirmed cases

of HCV infection reported in Massachusetts was further examined by age

and compared for the years 2002 and 2009 (Figure 2). The data shifted

from a unimodal age distribution in 2002 to a bimodal age distribution

in 2009, with the latter showing substantially more reports of HCV

infection among adolescents and young adults compared with the earlier

period.

(Enlarge Image)

|

Figure 1.

Rates of newly reported cases

of hepatitis C virus infection (confirmed and probable) among persons

aged 15–24 years and among all other age groups — Massachusetts,

2002–2009

|

<blockquote>

</blockquote>

Figure 1. Rates of newly reported cases

of hepatitis C virus infection (confirmed and probable) among persons

aged 15–24 years and among all other age groups — Massachusetts,

2002–2009

(Enlarge Image)

|

Figure 2.

Age distribution of newly reported confirmed cases of hepatitis C virus infection — Massachusetts, 2002 and 2009

* N = 6,281; excludes 35 cases with missing age or sex information.

† N = 3,904; excludes 346 cases with missing age or sex information.

|

<blockquote>

</blockquote>

Figure 2.

Age distribution of newly reported confirmed cases of hepatitis C virus infection — Massachusetts, 2002 and 2009 * N = 6,281; excludes 35 cases with missing age or sex information.

† N = 3,904; excludes 346 cases with missing age or sex information.

During 2007–2009, MDPH received 1,925 reports of new cases of HCV

infection among persons aged 15–24 years. Of these, 1,026 (53%) were

classified as confirmed cases of HCV infection; the remainder were

classified as probable. Although some clustering of cases was observed

in urban areas, cases were reported from all areas of the state,

including large metropolitan areas, suburban areas of Boston, smaller

cities, and rural areas. Cases occurred with nearly the same frequency

among men and women.

Of the 1,925 CRFs sent to reporting sources for completion, 1,448

(75%) were returned to MDPH, providing details of 802 confirmed and 646

probable cases. Of those returned, 252 (17%) CRFs did not have

sufficient information to assess risk, and of these, 148 (59%) contained

no risk data.

Of the total 1,448 CRFs returned, 1,357 (94%) included information on

race. Of these, 1,052 (78%) indicated cases among persons who were

white, 37 (3%) who were black, and 21 (2%) who were Asian; four

indicated cases among persons who were American Indian/Alaska Native,

and two indicated cases among persons who were Native Hawaiian or other

Pacific Islanders. Ninety-four CRFs indicated cases in persons reported

as being of unknown race, and 147 indicated "other" or multiple race

categories. Of 1,154 (80%) cases with ethnicity information, 98 (8%)

were among persons identified as Hispanic. Eight percent of the 1,448

cases with completed CRFs were among persons who were homeless or

incarcerated.

By far, the most common risk identified was IDU. Of 1,196 cases with a

reported risk history, 860 (72%) were in persons who reported current

or past IDU; of these, 719 (84%) reported injecting drugs during the

preceding 12 months. In addition, 445 (34%) reported some history of

intranasal drug use. All but 34 of the cases for which intranasal drug

use was listed also indicated IDU. Of the 719 cases for which IDU during

the preceding 12 months was reported, 615 (85%) were among persons who

reported heroin use, 220 (29%) cocaine use, seven (1%) methamphetamine

use, and 31 (4%) use of other drugs, including opiates other than heroin

(categories are not mutually exclusive because more than one drug could

be reported). Additional commonly reported potential exposures included

"other" blood exposures (24%) (further detail is missing for most cases

for which this was reported; for those cases with this information

included, a majority of "other" exposures listed were related to IDU),

tattoos (23%), and a history of incarceration (20%); however, most cases

involving these exposures were among persons who also were exposed

through IDU.

Editorial Note The Massachusetts surveillance data indicate an increase in HCV

infection cases among adolescents and young adults during 2002–2009.

These cases were primarily among non-Hispanic white residents in urban,

suburban, and rural communities. Although calculating an incidence rate

from the surveillance data or determining the duration of infection for

persons who tested positive for anti-HCV antibody is not possible, the

findings suggest that most persons aged 15–24 years with HCV infection

likely acquired their infections within a few years of being tested and

reported. Although similar increases in human immunodeficiency virus

(HIV) infection were not identified for this age group, increases in

reports of HCV infection among injection drug users might be a harbinger

of increases in IDU-associated HIV.

Other states have indicated similar increases in HCV infection among

adolescents and young adults. For example, in 2008, New York reported an

increase in HCV infection among persons aged <30 years in suburban

Buffalo.

[5] Since that time, surveillance data have indicated continued

transmission and possibly new activity in other areas of New York (Elena

Rizzo, New York State Department of Health, personal communication,

2011).

During the period when increases in HCV infection were being

observed, Massachusetts experienced a concomitant increase in heroin use

among adolescents and young adults. Data from MDPH-funded substance

abuse programs showed a rise in the percentage of admissions (for all

drug use) among persons aged 15–24 years, from 19% in 2002 to 23% in

2008.* Furthermore, the percentage of program clients who reported

needle use when admitted increased from 29% in 2002 to 38% in 2008 among

persons aged 15–24 years, whereas the percentage among all other age

groups during this same period remained relatively constant at

approximately 30%. Although the occurrence of IDU-associated HCV

infection has been documented for decades, the recent epidemic in

reported cases among adolescents and young adults and its apparent

association with increases in drug injection and sharing of injection

equipment in this population is a disturbing trend. Law enforcement data

suggest this trend might be occurring in other states. During

2002–2009, the estimated average annual number of heroin initiates in

the United States increased from 100,000 to 180,000.

† Law

enforcement reporting from the Great Lakes, Mid-Atlantic, New England,

New York/New Jersey, Southeast, and West Central regions also suggests

that heroin use is increasing, particularly among younger users.

§ Addressing the epidemic of HCV infection among adolescents and young

adults presents unique challenges in terms of education, outreach, and

other interventions. Studies have shown that the incidence of HCV

infection among injection drug users aged <30 years ranges from 10 to

37 cases per 100 person-years.

[6,7] Moreover, among adolescents and young adults who inject drugs, HCV

positivity has been associated with duration and frequency of injection.

[6] Adolescents and young adults might be more likely to share drug

equipment because of the nature of their social networks, which are

characterized by trust and sharing.

[6] The nature of these interactions must be taken into account when

developing educational materials. Adolescents and young adults are

likely to have participated in other risky behaviors before initiation

of injecting and might have multiple physical, mental, and emotional

health needs.

[8] The recent Institute of Medicine report on viral hepatitis and liver

cancer noted that younger injection drug users might be at highest risk

for seroconversion in the years immediately following initiation of

injection practices.

[2] The findings in this report are subject to at least four limitations.

First, the surveillance data only include information for persons who

have access to and obtain serologic testing and thus might

underrepresent the number of persons with HCV infection. This also might

explain, in part, the demographic patterns that were observed. Second,

efforts by MDPH to raise awareness of the increase in case rates among

this age group might have contributed to an increase in testing and

reporting of cases after 2007. Although data were not available to

ascertain whether this actually occurred, and if so, what the magnitude

of such an effect might have been, increases in the case rate among

adolescents and young adults in Massachusetts were evident in the years

before 2007 and, in fact, were more pronounced. In addition, recent

research on injection drug users showed that, although persons aged

18–24 years had the highest rate of being tested for HIV, they had the

lowest rate of HCV testing despite national recommendations for

counseling and screening of injection drug users.

[9,10] Third, differences by county of residence could not be determined

because of infrequent recording of residence information on laboratory

results not accompanied with a matching CRF. Finally, differences in

testing and reporting by county might also exist. Further studies are

needed to better characterize the population groups that are at

increased risk and those persons who are infected with HCV. Health-care

providers need to be encouraged to ask about risks for HCV infection,

especially IDU, and to screen patients at risk.

One important outcome of this study is that CDC, in collaboration

with state and local health departments, is examining HCV surveillance

data to determine whether similar trends are occurring in other

reporting areas. In addition, MDPH and CDC are conducting an in-depth

investigation of the causes of HCV transmission among adolescents and

young adults in Massachusetts to recommend and implement targeted

prevention measures.

This report highlights the important role of surveillance for HCV

infection and reporting of all laboratory tests positive for HCV, along

with the capacity to collect data of sufficient quality for meaningful

analysis of trends in transmission and disease. By 2010, 43 states

(including Massachusetts) and the District of Columbia required

reporting of all laboratory tests indicative of HCV infections.

¶ However, despite the laboratory reporting requirement, most states have

limited resources dedicated to surveillance of viral hepatitis and lack

capacity to investigate reported cases and forward reliable data to CDC

for national reporting. The Institute of Medicine noted this deficiency

in public health surveillance as a major weakness in the prevention of

viral hepatitis and liver cancer and recommended federal assistance for

states to effectively conduct surveillance for all forms of hepatitis C.

[2] This report also strongly indicates the need for expanded and

intensified hepatitis C prevention efforts targeting adolescents and

young adults. The Institute of Medicine notes that multicomponent,

comprehensive risk reduction programs are likely to be the most

successful at addressing HCV infection prevention needs of persons who

use illicit drugs. Some interventions that could be implemented include

access to sterile syringes and drug preparation equipment through

syringe exchange services, expanded school-based education that includes

viral hepatitis prevention messages, expanded harm reduction programs

directed toward young drug users, entry to drug treatment for young

injection drug users, and access to comprehensive health services that

include HCV testing and linkage to care.